A Day in the Life of a San Francisco Election

Being a poll worker allowed me to witness firsthand the flaws and the vulnerabilities within our election process

Please enjoy this guest post by Phaedra Fisher, a Sane Franciscan who also happens to be the author of “Vodka Diplomacy: And Other Adventures and Lessons in the New Russia.” She describes her book as “a personal account of a naïve, young woman who attempted to be a positive force for change in Russia during the chaotic mid-1990s.” (It’s a good read, I recommend it!)

I can vouch for all that Phaedra recounts below since we both signed up to be poll workers at the same polling station. It was my first time too.

On March 5th, 2024, I served as a poll worker for the election in San Francisco. This was my first time and it was an eye-opening experience. No, I didn’t witness anything that I would call outright fraudulent activity. But what I did see that day has given me a new perspective on the complexity of the current election process here in San Francisco, and how vulnerable the process potentially is.

While I have been voting my entire adult life, I have to confess that until recently I had not given the election process much thought. But with all the claims of election fraud in recent years and a very contentious 2024 election season heating up, I wanted to see the process firsthand. Or at least to witness what one can from the perspective of a single poll worker on election day.

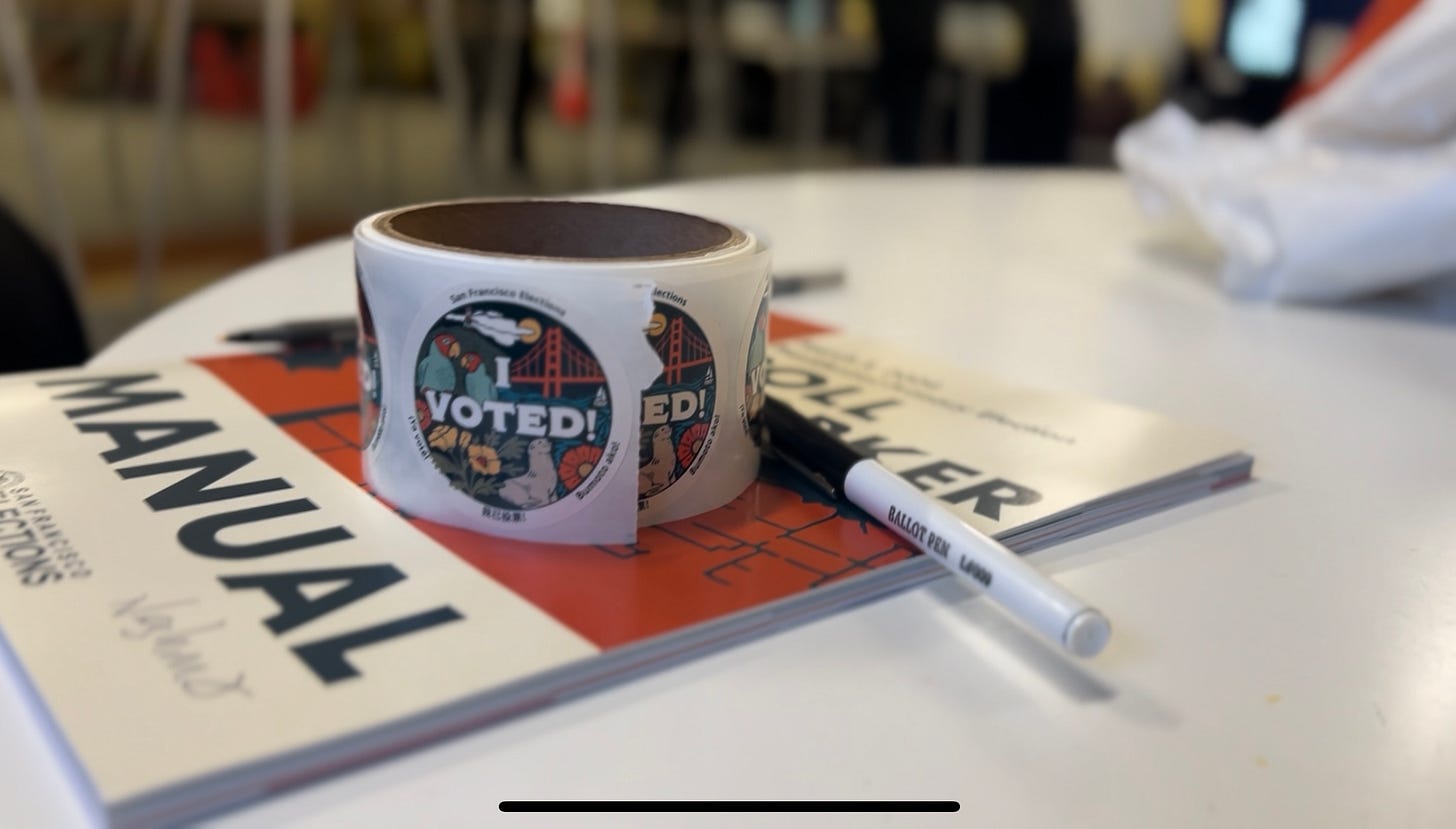

How to cast a ballot

First, some brief background. In San Francisco, there are three ways to cast a ballot:

Mail-in ballot

Vote in person

Provisional ballot.

For the mail-in ballot, all registered voters automatically receive a ballot by mail several weeks ahead of the actual election day. The voter can complete their ballot and return it in the envelope provided by either dropping it in a mailbox, at a designated drop-off box or, on the day of the election, the voter can walk into the polling station and drop their ballot in the red box in person.

To vote in person, a person must be on the roster of registered voters for the precinct. A poll worker asks for the person’s name and address, and if a match is found, they are given a paper ballot and a blue privacy folder. The voter completes their ballot by marking it with a pen or pencil on a small table with a privacy screen. After that they feed their ballot into the counting machine.

If someone wants to vote in person, but their name is not on the roster for the precinct, they are given a ballot together with an envelope for a provisional ballot. Once completed, the voter drops their envelope into the red ballot box.

Casting my own vote

This election season, I decided to vote in person at San Francisco City Hall ahead of the actual election day, March 5th. As I was voting in a location other than my own precinct, I received a provisional envelope with my ballot.

Affixed to the outside of the envelope was a sticker with my name, address, and political party registration. I was stunned. Yes, I would complete the ballot in secret, but why was my party affiliation printed on the envelope? My mind was already taking note of all the potential weaknesses in the process.

After I dropped my completed ballot in the ballot box, I walked up to the front desk for the office of the department of elections and asked, “Why is party affiliation on the outside of the envelope?” A helpful woman at the counter took me on an impromptu tour of the facility and showed me the enormous high-speed counting machine in a nearby hall. She explained that the voting machine has different settings for each ballot type: Democrat, Republican, Libertarian, etc, and that part of the process is to separate the envelopes into batches by party registration and then run each batch separately through the machine.

Threat modeling

I would encourage you to think through all the possible ways this process could be exploited to engineer the results of an election. In software this is called “threat modeling.” It is a standard exercise in software design that I’m sure you just take for granted, even if you have never heard of the term.

For example, a basic threat modeling exercise for the payment app Venmo would walk through the question, “how can you be sure that you have selected the right person for payment?” In response, the team at Venmo have delivered several safety features, such as: requiring the last four digits of the recipient’s phone number, enabling the recipient to generate a QR code, or supporting a profile photo. Each of these features gives the sender confidence that they have selected the correct recipient.

So what could be problematic with the political party preference on the outside of the envelope? A human being reviews the signature on the outside of each provisional and mail-in ballot envelope and compares this signature to the signature on file for the voter registration and from prior elections. This human being makes a judgment about whether to accept the signature as valid or reject the ballot.

Could the party on the envelope influence the person’s decision for whether to accept the ballot?

And also when checking the signature, is the voter’s party preference displayed to the election worker? (I actually don’t know, but if so, then this is another opportunity for bias to sway judgment).

Then look at the counting machine:

Who knows what the software is actually doing? I was just told that there is a separate setting per political party! What does that setting do?

On to the election day itself

I arrived at my assigned precinct location shortly before 6:00 am. The Inspector (aka lead poll worker) was already setting up the counting machine. He had broken all the seals on the machine before anyone arrived. He muttered to himself, “Oh yeah, I guess that was supposed to be witnessed,” but pushed on regardless. This lax attitude set the tone for the day.

From the moment the polls were open at 7:00 am, a near-continuous stream of people came through the precinct. Most just strolled through to drop off their mail-in ballot and were on their way. Some dropped off not just one, but handfuls of mail-in ballots.

As people came to vote in person, I asked for their name and address and confirmed them against the roster. Most people offered to show me a photo ID and were surprised when I responded with, “You actually don’t need a photo ID to vote in San Francisco.” Some actually gasped with wide, alarmed eyes. The voters then entered their signature on the roster and received a ballot.

That’s the situation here in San Francisco. No ID, just a signature. How do we know that these people are who they say they are? The roster of people registered to vote in a precinct is posted outside the polling station. In addition, the official process is that once an hour the poll workers are supposed to cross off the names of those who have already voted. Towards the end of the day, it would be very easy to see who had not voted yet, memorize a name and address and just walk in and ask for a ballot.

A significant number of people attempting to vote in person were not on the roster. Apparently the precinct boundaries had changed recently. Many voiced displeasure with the provisional ballot envelope, including objections to the party preference being on the outside of the envelope.

And then one woman walked into the polling station and declared: “I am not registered to vote but I would like a ballot.”

The official poll worker training and manual did not cover this situation, so I called the San Francisco Department of Elections poll worker helpline. I was instructed to give the woman a ballot together with a provisional envelope. I asked what additional documentation she needed to provide to confirm her eligibility to vote in this election.

The answer I received: “No, you do not need to ask for any ID. We will check the information on the provisional ballot envelope against our records.”

I asked: “But what records are you evaluating? She already said that she is not a registered voter.” The response was simply: “We will evaluate our existing records.”

And so I was obliged to give this woman a ballot of her party choice together with an envelope for the provisional ballot. I did not collect any information from her. I have no idea who she is and never will.

And bear in mind, this was the one woman who actually told me that she was not registered to vote. No evidence of citizenship or identity was asked of the other 229K+ people who participated in the March 5th elections here in San Francisco. What is stopping the thousands of non-citizens in San Francisco from voting? As far as I can tell, the answer would be “absolutely nothing.”

I highly encourage everyone to participate in the election process as a poll worker or election observer in some capacity. It is one thing to read about the election processes and quite another to actually see events played out by real people in real time.

A variety of individuals

Individual personalities are fascinating and we saw a wide variety that day.

One man entered the polling station and declared loudly:

“All the political parties are corrupt! How do I renounce party membership? Can I still vote?”

I helped him with the form to update his voter registration to “no party preference” and then asked him which ballot he wanted to receive. He was baffled that now, even with “no party preference,” he could STILL receive a primary ballot tagged to a political party. This would contain the presidential primary options, but not the local central committee candidates. He thought for half a second and responded. “Nope. No party at all. I am done with political parties.”

Another memorable encounter was with a woman with a Slavic accent. She wasn’t on the roster so I needed to give her a provisional ballot. I asked for her party registration so that I could give her the correct ballot. “I just want a ballot,” she said quietly. I explained that in fact there were six different varieties of ballot based on party registration, plus four varieties for those with no party preference. When voting provisionally you need to either vote with the ballot of your party registration, or change your party registration on the day.

The woman looked at me with alarm and whispered her party preference. She then took a deep breath and said: “How is this a secret ballot if I need to declare my party preference to everyone here?”

And I have to say, based on my own voting experience described at the beginning of this account, that I empathize with her. No one should be forced to state anything about their political views in public. However, here in California, one’s party registration is a matter of public record. Back to my earlier point about threat modeling, how many nefarious ways could that information be used to pressure or silence targeted people? The woman with the Slavic accent almost certainly had her homeland’s history in mind during our brief conversation.

Another incident provided a different example of inappropriate pressure on individuals regarding their political preferences. A loud man entered the polling station with a meek woman (presumably his wife) at his side. He requested ballots for both of them. The couple then proceeded to a polling booth together where they stood shoulder to shoulder completing the ballots. From the bits that I could not help but overhear as well as body language, it was clear that the man was either completing his wife’s ballot for her, or instructing her what to write field by field. I expected in this case that the Inspector would intervene, but he did nothing. I fumed that the scene was exactly what should NOT happen. Every individual should have their own ballot and the privacy to complete this exactly how they want. As the couple left, the woman gave me a desperate glance. I hesitated a moment too long and lost the opportunity to attempt to talk with her separately about what had just happened.

I was now on high alert for any inappropriate pressure on voters and was determined to prevent a repeat of this incident.

The case of “Bob”

In the early afternoon a blind man entered the polling station, escorted by a man I will call his “helper.” The blind man was older and physically fragile. In addition, he seemed to have some mental challenges. The helper requested a ballot for himself and one for the blind man (who I will call “Bob”). The helper was about to take both ballots to a voting booth when I intervened. I said to Bob: “This is your ballot. You have the right to complete your own ballot.”

The helper objected: “I know how he wants to vote. I can do this for him.”

I responded: “This is Bob’s ballot. It needs to be his decision about how this is completed.” Another poll worker politely but firmly escorted the helper to the side while I continued my conversation with Bob.

Each polling station has assistive technology for those who may need it. Bob was not familiar with the concept of assistive technology, so it became very quickly apparent that I would need to read the ballot to him and that he would need to instruct me how to complete the ballot on his behalf. I shared this plan with Bob. The helper protested that this was going to take too long.

I asked Bob: “Is there anywhere you need to be later? Is there a deadline we are working against?”

Bob very pleasantly replied: “No. I have all day.” So I sat with him and literally read out every single word on the ballot and noted his decision on each candidate. The March 2024 San Francisco ballot was four pages long. It included the presidential primary, eight additional races, plus one state initiative and seven local initiatives. The helper voiced his exasperation that I truly was reading every word on the ballot. Finally Bob succumbed to pressure. His willpower faded and he asked the helper for his recommendations. The helper handed me a printed voters’ guide.

I refused to simply complete the ballot the way the voter guide was printed as I wanted to be sure that Bob understood what he was voting for. So I continued to read each ballot measure and then asked him: “Do you want to vote Yes or No?” I offered to re-read the initiative if necessary. I reminded him that there was no rush. Together we could ensure his ballot was completed exactly the way he wanted. But if he wanted to know what the voter guide recommended on any point, I would read it to him.

Over an hour later, we were finally done. I was mentally exhausted from the exercise but glad that I had done what I could to preserve an independent vote for at least one person who might otherwise have been bullied to comply with another’s wishes.

For the rest of the day, as I watched people come through the precinct and drop off handfuls of mail-in ballots, I had to wonder: “Who are these people and why do they have so many ballots?” Yes, someone in a long-term relationship may entrust their partner to drop off a ballot for them. But why would someone drop off four ballots? How did they convince someone to delegate this fundamental element of citizenship?

An emergency

One more scene with a voter is worth noting. The mother of one of the poll workers, a woman who appeared to be in her early- to mid-sixties, walked into the precinct with confidence. She went to stand at a polling booth to vote. After a few minutes she suddenly said that she needed to sit down, and the daughter helped her relocate to a nearby table. Once seated, the woman then stared forward, dropped her pen, and swayed back and forth. The daughter leaped to her aid and called for others to help her mother safely to the floor. Did the mother faint? Or was this a more serious medical emergency? No one knew. The daughter cried out, “Call 911!”

The room erupted into chaos. The Inspector wanted to close the polling station! I told him that we had to keep the polling station open, but made the suggestion that we might position poll workers outside the room to tell voters that there was a medical emergency underway so that they could decide what to do. This situation was not covered in any of the training manuals so the Inspector left the room to call the poll workers’ hotline number for advice.

When the first responders arrived, they tried to clear the room. At this point there were a few people in voting booths, plus of course the ballot box and a stack of blank ballots. The Inspector had already left. Some of the other poll workers complied with the first responders’ request. But under no conditions was I, nor the friend I had signed up with to become a poll worker, fine with simply abandoning the active polling station.

(Okay, I would probably have left if the building were on fire, but even then I would have tried to figure out how to retain the integrity of the ballots under my care.)

My poll worker friend and I flattened ourselves against a wall so that we would be out of the way of the first responders while retaining visibility for everything going on in the polling station. The Inspector was outside the room. One of the other poll workers was now outside explaining the situation to those approaching. At first another poll worker thought the best approach would be to offer to transport any mail-in ballots to the ballot box, but I objected — only the voter or their delegate should touch the ballot! She quickly agreed and then coached those with drop-off ballots to scurry in and out of the room as fast as possible. She also encouraged those who wanted to vote in person to simply wait a short while, since we were not officially closed if they really needed to vote at that moment. During this time, I believe that one of the other poll workers was on break and I have no recollection what was going on with the remaining poll workers who were at my precinct that day. My poll worker friend and I might have been the only people in the room with the first responders, the mother and her daughter who was attending to her, a few in-person voters, and the ballots. The mother’s ballot sat on the table, unfinished. As soon as the first responders left, I sealed her ballot in her provisional envelope (which she had already completed) and placed it in the ballot box. All citizens have the right to vote and I was determined that even a medical emergency would not prevent this woman from doing so.

To wrap up the above anecdote, we were all relieved to receive the news later in the day that the mother had been treated and released from the hospital. I don’t know her exact medical diagnosis (nor is it any of my business) but I am glad that this part of the story had a happy ending. And I am glad that at no time the polling station was left unattended.

Closing time

After a very long day, the polls closed at 8 pm. The poll workers and Inspector moved rapidly into close down mode and end of day counts. If everything went well, the total number of blank ballots at the beginning of the day would equal the number of ballots fed into the counting machine, plus provisional ballots, plus ballots marked as “spoiled,” plus remaining blank ballots. This count did balance at our precinct and I was relieved.

The second count was to compare the number of signatures on the roster to the number of ballots counted by the machine. This should be the same number as only those people on the roster should feed their ballot into the counting machine. Anyone not on the roster should receive a provisional envelope and put their ballot in the red ballot box. It turned out there were three more in the count for the machine than signatures on the roster. Not a huge difference as there were about 187 in person votes, but enough to show that there were some cracks in the process execution on the day. The Inspector brushed this off with the comment: “This is my 17th election. This happens.”

The closing process includes packaging and sealing all the official output from the election and documenting the chain of custody handovers to the Sheriff’s Department and to the FED. This whole process was a bit of a blur and chaotic and I don’t have good notes to describe exactly what happened here. I will refrain from any comment other than I have no reason to believe any fraud was committed at my precinct, but the whole process was incredibly chaotic as we searched to find the right seals and bags and package everything correctly.

Finally, after a very long day that started at 6:00 am and finished at 9:45 pm, we were done and my day as a poll worker had ended.

I share all these anecdotes to give a bit of color for what actually happens during an election. Or at least what I personally witnessed as a poll worker at one of the 501 polling stations in San Francisco on March 5th, 2024. Each of the other polling stations across the city, state, and country undoubtedly have their own unique scenarios as well.

Questions

I offer some key questions for consideration:

How can we ensure that our elections are free and fair?

How can we maximize access to voting, while minimizing the potential for fraud or abuse?

How do we ensure that only citizens are voting?

What are the risks with mail-in ballots?

What are the risks with electronic counting machines?

Why are some politicians deeply opposed to requiring government IDs and in person voting on paper ballots?

How can we fortify the secret ballot? If our name and party affiliation are on the outside of an envelope, is our ballot truly secret? And with a mail-in ballot, the government can know exactly who they sent which ballot to. How can I respond with confidence that my political preferences are not tracked and used against me?

Get involved

I encourage everyone to evaluate the voting process with critical eyes and, better yet, get involved yourself as a poll worker, an election observer, or directly speak out for how the election processes can be improved.

And in closing, a reminder from Thomas Jefferson:

“The price of freedom is eternal vigilance.”

We must all do our part. Ask questions, and demand accountability. Otherwise we will all soon be that Slavic woman who was alarmed to disclose her party registration in public.

Now I turn to you, Sane Francisco readers, and ask how you think we might best solve these challenges. ~PF

Thank you for reading Sane Francisco. If you find value in my work, please consider a paid subscription or make a one-time donation by buying me a coffee. Your support is very much appreciated! 💛

Phaedra, thanks for writing about our long day together as poll workers. So much happened during those 16 hours, I’m glad we were both there to observe it all...

What would I do to improve the process?

1. Go back to manual counting.

2. The ballots should be counted before leaving each polling station.

3. IDs necessary!

Thank you for your service! Sounds like voting is as "safe" and "secure" as Covid vaccines were "safe" and "effective."